Author Spotlight:

Linda Dryden

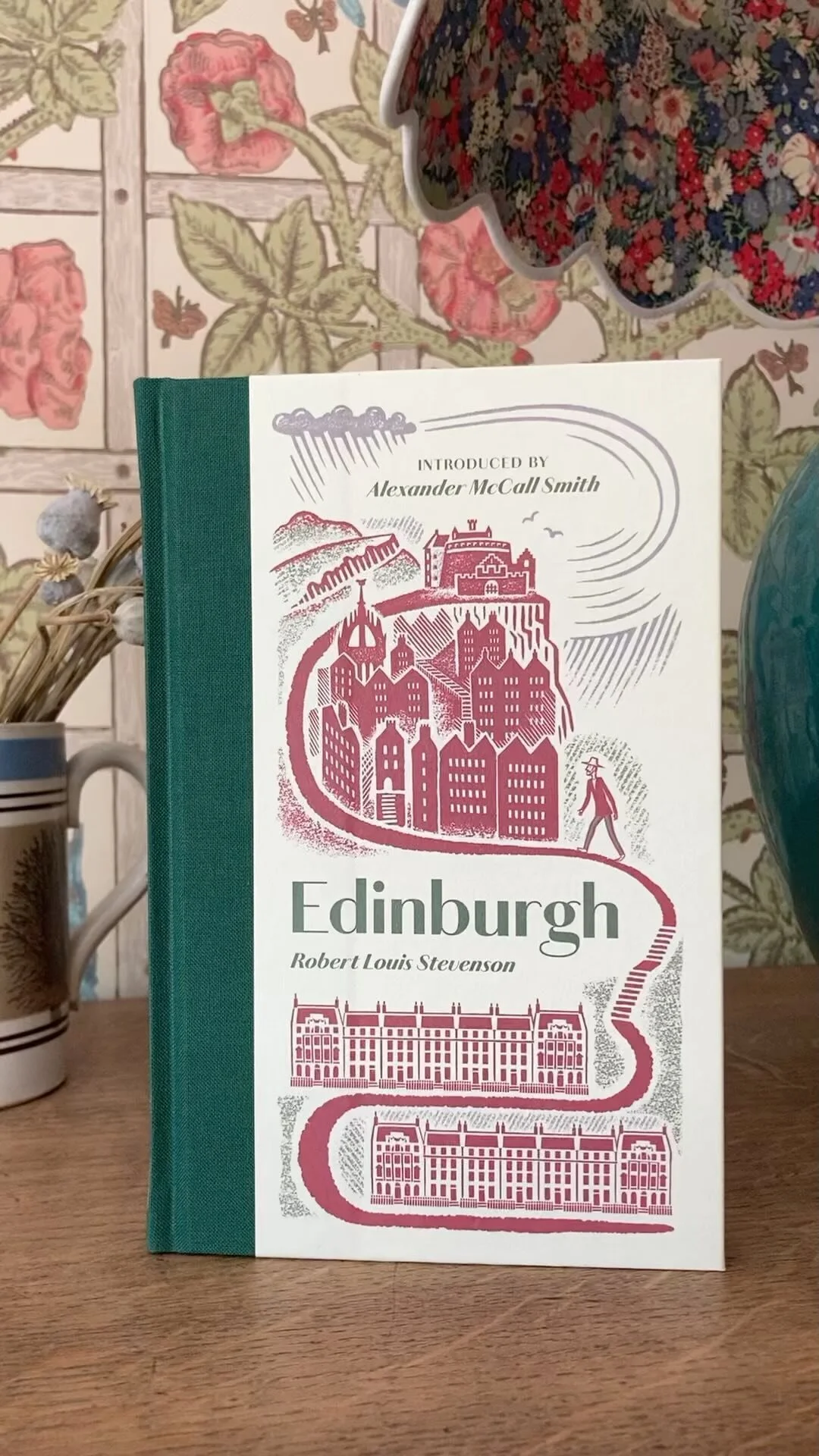

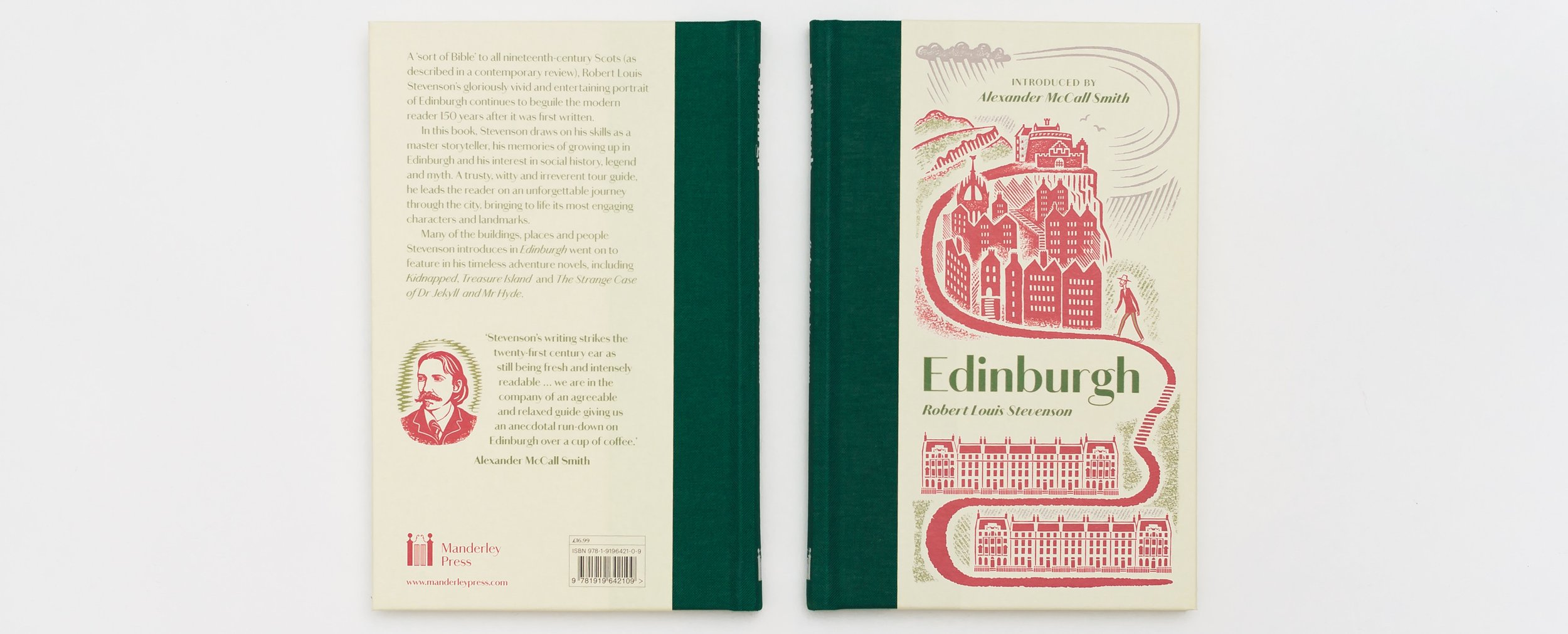

If you couldn’t make it to the book launch for Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes (which took place at the Edinburgh Bookshop on 13 November 2021), you can now read Linda Dryden’s keynote speech from the comfort of your own sofa!

Published exclusively on manderleypress.com, below is the transcript of Linda’s introduction to the new edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes. It is particularly fitting that this talk was delivered on what would have been Stevenson’s 171st birthday.

Edinburgh truly is a city of the imagination. In our own time Ian Rankin has explored its darker underbelly, the crime, corruption and deprivation that lurks beneath its elegant, seemingly serene surface. Alexander McCall Smith, whose excellent introduction graces this beautiful volume, uses Edinburgh’s New Town and its residents to satiric effect in his 44 Scotland Street series. In its stunning location, with its striking architecture and colourful history the city offers a compelling, fertile playground for the imagination. It is no wonder that Edinburgh became UNESCO’s first City of Literature in 2004.

The city’s literary heritage is nowhere more rich and potent than in the literary imagination of Robert Louis Stevenson and we are gathered here this evening to celebrate Stevenson’s paean to the city of his birth, Picturesque Notes. This book is a writer’s loving homage to place of his birth and I can think of no greater honour a writer could give to his city than volume such as this. If you will excuse the expression it is truly a warts and all account of the place and its inhabitants as Stevenson knew it in his childhood and early adulthood.

For Stevenson truly was a son of Edinburgh. From Howard Place, where Stevenson was born in 1850, the family moved to Inverleith Terrace by the Royal Botanic Gardens, and later to the grander terraces of the New Town in Heriot Row. Stevenson was the scion of a wealthy and renowned family of lighthouse builders and enjoyed all the privileges that accrued to such a heritage. He lived in the most luxurious surroundings that the Edinburgh bourgeoisie could afford, but he was alive to the world beyond his own gilded circle. And thus in Edinburgh Picturesque Notes he takes his reader on a journey through the winding lanes of the Old Town, the geometric symmetry of the New Town and leads us out into the suburbs towards the Pentland Hills that frame the city to the south and finally to Swanston Cottage. The book is to all intents and purposes a love letter to the city of his birth.

Edinburgh, of course, features in so many of Stevenson’s works, but especially in Weir of Hermiston—the hero Archie Weir and his parents live in a house on George Square. I think I identified the exact house once—it is one of those on the south side of George Square, behind the University library and backing onto the Meadows. Now offices for the University of Edinburgh, it would once have been one of the grander Edinburgh residences, as befits Weir the elder, the most senior judge in Scotland. And Archie, like Stevenson, studies Law at the University and is a member of the Speculative Society.

The sights and historic buildings of Edinburgh also feature prominently in St. Ives, another unfinished novel set during the Napoleonic wars. Edinburgh Castle is a key location where the eponymous St. Ives is imprisoned and subsequently escapes down the southern rock face, catching glimpses of the sprawling night-time city below as he scrambles down: ‘I looked up: there was nothing above me but the blackness of the night and the fog. I craned timidly forward and looked down. There, upon a floor of darkness, I beheld a certain pattern of hazy lights, some of them aligned as in thoroughfares, others standing apart as in solitary houses.’ (P. 37). In this description Stevenson imagines how the city appeared over half a century before he was writing. From his vantage point high on the Castle rock he sometimes catches glimpses of Princes Street, which he says ‘serves as a promenade to the fashionable inhabitants of Edinburgh’, and he follows their movements along the street ‘as they passed briskly to and fro—met, greeted, and bowed to each other—or entered and left the shops, which are in that quarter, and, for a town of Britannic provinces, particularly fine’ (P. 51). In a sense it is an image of the city centre that has changed little in the intervening century and a half.

Much later he describes a Sunday in the north of the city. They strolled ‘past the suburbs, and on into the streets of the New Town, which was as deserted and silent as a city of the dead. The shops were closed, no vehicle ran, cats sported in the midst of the sunny causeway; and our steps and voices re-echoed from the quiet houses. It was the high-water, full and strange, of that weekly trance to which the city of Edinburgh is subjected: the apotheosis of the Sawbath; and I confess the spectacle wanted not grandeur, however much it may have lacked cheerfulness. There are few religious ceremonies more imposing. As we thus walked and talked in public seclusion the bells broke out ringing through all the bounds of the city, and the streets began immediately to be thronged with decent church-goers’ (P.228). Stevenson’s knowledge of the Edinburgh of his youth is treaded through these passages, even though they are staged decades earlier.

The Edinburgh of the imagination is a constant presence in Stevenson’s fiction. Even Jekyll and Hyde, a novel ostensibly set in London is inspired by Edinburgh, and many claim that the setting really is Edinburgh. I have some sympathy for that perception. In the opening sequence of the novella, Enfield describes to Utterson his encounter with Hyde: ‘I was coming home from some place at the end of the world’, says Enfield. Those who know the city will know of the World’s End pub. A hostelry that Stevenson certainly frequented, The World’s End is situated at what was once one of the portals to the city—it is positioned at was once literally, the end of the world in Edinburgh terms. It is not too much of a stretch to suggest that some sense of Stevenson’s own night-time forays into the old town filter through into Enfield’s narrative.

And he continues to describe the scene of Hyde’s trampling of the young girl: ‘my way lay through a part of town where there was literally nothing to be seen but lamps. Street after street, and all lighted up as if for a procession and all as empty as a church—till at last I got into that state of mind when a man listens and listens and begins to long for the sight of a policeman.’ Street after street of lamps is certainly how the New Town looks, and whenever I read that passage I can also imagine the scene taking place on the Mound. Then there is Jekyll’s house: it is clearly a Georgian house in the style of the New Town home of the Stevensons, with its fanlight over the door and the fact that unlike the others on the terrace, it has not been subdivided into flats. Utterson is ushered by Poole into the hall which is ‘paved with flags’, warmed by an open fire and ‘finished with costly cabinets of oak,’ all reminiscent of many a Georgian house in Edinburgh.

Edinburgh was the scene of much adolescent carousing, as Stevenson’s many biographers have noted. The LJR (Liberty, Justice, Reverence) society which Stevenson formulated with his friends and fellow students would meet in the pub in Advocates Close, probably what is now the Jolly Judge. His evening forays down the Royal Mile, in his famous velvet jacket, are the stuff of legend—it is well known that Stevenson was a regular in many of Edinburgh’s profusion of public houses. Drinking was very much part of Stevenson’s experience of his city, and in Picturesque Notes he gives a vivid, lively and amusing account of New Year’s Day carousing:

Auld Lang Syne is much in people’s mouths: and whiskey and shortbread are staple articles of consumption. From an early hour a stranger will be impressed by the number of drunken men: and by afternoon drunkenness has spread to the women. With some classes of society, it is as much a matter of duty to drink hard on New Year’s Day as to go to church on Sunday. Some have been saving their wages for perhaps a month to do the season honour. Many carry a whiskey bottle in their pocket, which they will press with embarrassing effusion on a perfect stranger. It is inexpedient to risk one’s body in a cab, or not, at least, until after a prolonged study of the driver. The streets, which are thronged from end to end, become a place for delicate pilotage. Singly or arm-in-arm, some speechless, others noisy and quarrelsome, the votaries of New Year go meandering in and out cannoning one against another; and now and again, one falls and lies as he has fallen.

Plus ca change….this could almost describe what is going to happen in this same city in a few weeks’ time as we ring in 2022. This as affectionate and indulgent a description of the drunken denizens of a city as anything to come from the pen of Dickens. But Stevenson doesn’t pass moral judgement, he doesn’t sneer or condemn: rather, he seems to be saying ‘this is how it is—here is a picture of Edinburgh at New Year.’ And for me it is as evocative as if he had painted the scene.

An anecdote, told to me by that wonderful veteran Scottish actor John Cairney sticks in my mind and gives a real sense of Stevenson’s movements across Edinburgh. His friend, the poet and prominent literary figure, W. E. Henley, was in the Royal Infirmary having had part of one leg amputated as a result of tuberculosis of the bone. John told me how Stevenson used to regularly visit Henley in the hospital and read to him. Eventually he got fed up with the inadequate seating in the hospital room so decided to bring in a comfy armchair from Heriot Row. John described Stevenson carrying the chair on his back across Princes Street, up the Mound, over George IV Bridge and into the hospital—all so that he could be comfortable over the long hours with his friend. Of course Henley is also famous as the inspiration for Long John Silver. In a letter to Henley he wrote: ‘I will now make a confession: it was the sight of your maimed strength and masterfulness that begot Long John Silver … the idea of the maimed man, ruling and dreaded by the sound, was entirely taken from you.’ And Cramond Island, a place RLS knew well is generally thought to have provided him with the geography of Treasure Island, as Alexander McCall Smith notes in his Introduction. As for the Admiral Benbow pub, it is certainly modeled on the Hawes Inn at South Queensferry.

And this brings me back to Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes. I don’t want to dwell on the book itself—we would far rather you immersed yourselves in its wonderful reflections on this beautiful city. But one or two comments are worth drawing your attention to. For example, Stevenson proudly describes the New Town as ‘what Paris ought to be’—his derogatory remarks about Paris are probably no longer tenable, but the parallel remains compelling. He says that the Calton Hill monument is ‘an imposing object’ that gave ‘Edinburgh, even from the sea, that false air of a Modern Athens’; and Edinburgh Castle is ‘a Bass Rock upon dry land, rooted in a garden, shaken by passing trains, carrying a crown of battlements and turrets, and describing its war-like shadow over the liveliest and brightest thoroughfare of the new town’. For Stevenson Edinburgh thrives as a modern European city: ‘this profusion of eccentricities, this dream in masonry and living rock, is not a drop-scene in a theatre, but a city in the world of every-day reality, connected by railway and telegraph-wire with all the capitals of Europe.’ It is a fitting irony in a post Brexit world to hear the city described in that context, and a reminder of our long established relationship with Europe—Stevenson’s frequent mention of European capitals, and his continental travels reinforce his sense of himself as not only a Scotsman, but as a citizen of Europe.

Stevenson was alive to Edinburgh’s caprices and contrasts. If the New Town rivaled Paris, the Old Town was ‘the liver-wing of Edinburgh’: ‘And what a picturesque world remains untouched! You go under dark arches, and down dark stairs and alleys. The way is so narrow that you can lay a hand on either wall; so steep that, in greasy winter weather, the pavement is almost as treacherous as ice.’ And, to be sure, it was the city’s inclement weather that drove the ailing Stevenson to warmer parts. Of the Edinburgh winter he wrote: ‘For some constitutions there is something almost physically disgusting in the bleak ugliness of easterly weather.’ He says that the ‘weather is raw and boisterous in winter, shifty and ungenial in summer, and a downright meteorological purgatory in spring’, concluding that for those who like clement climes, ‘there could scarcely be found a more unhomely and harassing place of residence’. And so it proved to be for Stevenson.

Ill health, love and a life-long wanderlust lead Stevenson far away from his beloved Edinburgh, first to Europe, then to America in pursuit of Fanny, and finally to Australia and the South Pacific where he set up home in Samoa, built his own elegant villa at Valima, and became known by the local population as Tusitala, the teller of tales. At Valima he installed his wife Fanny, his widowed mother and the rest of his extended family. Much of the furniture from the family home at 17 Heriot Row was even shipped over and if you look at some of the pictures that exist of his time in Samoa on the Stevenson website you will see how even in the tropics he recreated a sense of what the interior of his Edinburgh home would have looked like.

He left Edinburgh for the last time in May 1887, and never returned, but even in far off Samoa Edinburgh was never far from his thoughts. Despite his wanderlust and his love of the South Seas, Stevenson’s thoughts always turned homewards. Absence sharpened his perception, and in exile, Stevenson’s imagination returned time and again to Scotland and to Edinburgh. What he chose to record in Picturesque Notes reveals to us a complex weave of affection, nostalgia, resentment, and alienation that characterises Stevenson’s experience of, and relationship with his place of birth. These emotions were mellowed by time and distance into a moving homage to the land and city of his birth in Weir of Hermiston. The book was left unfinished by his untimely death at Valima in 1894. It is prefaced by a poem dedicated to Fanny, yet reading the opening lines, one could be forgiven for thinking it is really Edinburgh that he is honouring:

I saw the rain falling and the rainbow drawn

On Lammermuir. Hearkening I heard again

In my precipitous city beaten bells

Winnow the keen sea wind. And here afar,

Intent on my own race and place, I wrote.

My precipitous city: there can be no doubt where Stevenson’s heart lies. Even while reveling in the exoticism and the clement weather of his tropical island, his imagination is drawn back to the wind-battered, rain soaked, haar-plagued streets and wynds of the place of his birth. His nostalgia for the city is palpable: ‘Intent on my own race and place, I wrote.’ In this verse of dedication, he signals incontrovertibly, his investment in the city and the sense of place with which the novel is imbued.

On 5 June 1893, Stevenson had written from Samoa to S. R. Crockett: ‘I shall never see Auld Reekie. I shall never set my foot again upon the heather. Here I am until I die, and here I will be buried’. This melancholy reflection on his destiny was only too prophetic as he died the following year having never returned to Edinburgh.

I want to close this talk by reminding everyone of the significance of 13 November. When I first arrived in Edinburgh in 1996 I was surprised at how little recognition and celebration of Stevenson was in evidence in the city. Sir Walter Scott seemed to be everywhere apparent, but Stevenson could barely be seen. I thus set about creating the RLS website with a grant from the Carnegie Trust and then began work with Ali Bowden and Anna Burkey and others on the steering committee to make the case for the UNESCO City of Literature. Once we had achieved that ambition our thoughts turned to how to celebrate Stevenson within our new UNESCO context. Inspired by Dublin’s celebration of James Joyce, Bloom’s Day, we set about making Stevenson’s birthday, 13 November, an annual celebration which we named RLS Day. Today we have reached the tenth anniversary of RLS Day in Edinburgh, and I can think of no better way to celebrate this milestone than by launching this lovely new edition of Stevenson’s homage to his city, Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes.

Linda Dryden is Professor of English Literature in the School of Arts & Creative Industries. She started her academic career at Edinburgh Napier University in 1998 having received her PhD, entitled ‘Romance and Anti-Romance in Conrad’s Malay Fiction’, from Loughborough University in 1996. She has published three monographs: Joseph Conrad and the Imperial Romance (1999), The Modern Gothic and Literary Doubles: Stevenson, Wilde and Wells (2003), and Joseph Conrad and H.G. Wells: The Fin-de-Siècle Literary Scene (2015), all published with Palgrave. Linda created and manages the Robert Louis Stevenson website (www.robert-louis-stevenson.org), and is co-Editor of the Journal of Stevenson Studies. She has published over 40 journal articles and book chapters based on her interests in Conrad and the literary concerns of the fin-de-siècle. Linda is the Director of Research for the School of Arts & Creative Industries and also the Director of the University’s Centre for Literature and Writing (CLAW). She was the Editor for the Wordsworth Editions of the works of H. G. Wells and is editing The Lost World for the new Edinburgh Editions of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.